When the Rain Came

Summer 1999. I am working and earning good money as a self-employed carpenter. The kids are doing well in school and Teresa, my wife, has signed up at our local college to take a course that will lead her to university, where she will study for her nursing degree. Things are on the up. Even my beloved Manchester United have done well, winning the FA Cup, The Premier League, and the European Champions’ League Cup.

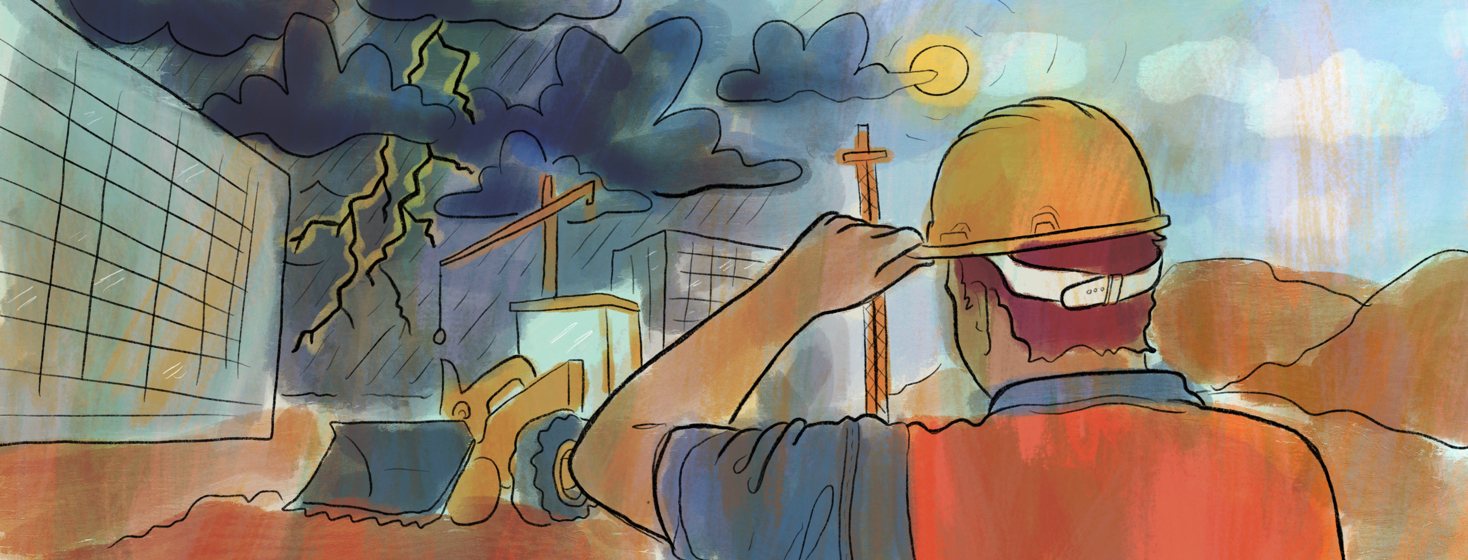

But then things start to change. I find myself waking in the mornings with pains in my joints and feeling exhausted, like I haven’t slept all night. Getting out of bed is difficult. It hurts when I move. But then, my job is a physical one and aches and pains are an occupational hazard. I say nothing to Teresa because I know she will worry. I say nothing when I get to work. No one on site wants to hear about it and even if they did, they wouldn’t know what to say.

Shows of affection or sympathy are rare among the men I work with. In any case, if word gets around that I’m struggling, I’m less likely to be offered work later. No one wants a broken builder. To get through the day, I take prescription pills – given to me by a well-meaning relative. Strong anti-inflammatories washed down with over-the-counter painkillers. Nothing works. The pain increases and I notice I am losing mobility in my neck. I struggle to turn my head from side to side. Looking up or down is a problem too.

By the end of year, I have been told I have ankylosing spondylitis – a disease I’ve never heard of. I remember the specialist who told me. I remember her name. I remember her words, kind enough, but devastating.

I am pulverized.

Anaesthetized.

Numb.

She tells me I must give up my job. Find something easier. No more building for you, she says. No more site work for you. She doesn’t say, no more wages for you. No more self-respect for you.

It was a mild day and there was an old wooden bench outside the hospital. One of those timber-slatted benches that has a little brass plaque screwed to it with the name of a deceased man or woman on it. A bus goes by. A young woman crosses the road, a small child holding her hand. An old man, helped by his wife, makes his way slowly into the hospital. The world is moving all around me, just as it was when I'd arrived. Nothing has changed. Nothing at all. Only me. My life has changed. And there is nothing I can do about it. I can't press the rewind button. Can't say, wait, wait, I’m not ready. Let’s try that again. Only this time don’t, don’t, don’t tell me I’ve got a disease I’ve never heard of. Don’t tell me my working life is over. Don’t tell me I have to go and let my wife know I am not who I was when I left the house this morning.

I am irreversibly flawed

I sit on the bench, and I roll a smoke and I spark it up and then I cry. Not sobs. Someone has to die before I sob. But looking back, someone did die. Right there on that bench. The old me died. The healthy me died. The strong me died. And so, the tears roll down my face and drop to the pavement at my feet.

How can I go home and tell what I have to tell? We have a mortgage, bills, and young children. I think then about men who suddenly vanish. Who disappear, leaving behind them bewildered loved ones. You see their lost faces sometimes on the side of milk cartons as you sit down to eat your morning cereal. I’d always thought, what strange men. Men with dark secrets to hide from their families. I’m not so sure now. Not so sure they are strange at all.

I am emasculated

The balance has shifted away from me. The equilibrium that is the foundation of my marriage is out of kilter.

I am exposed.

Disadvantaged.

Vulnerable.

It flits across my mind that Teresa might leave. Because, let’s be honest, when a person is diagnosed with a disease like AS it isn’t just them that gets it, is it? It’s their partner, too. In those early days I think I suffered a kind of temporary madness. An irrationality that seemed all too real to me at the time. I thought I would lose her. And my children too.

Summer 2021

Teresa and I are going out for the evening. I am upstairs getting ready. The radio is playing in the corner of the room and Rod Stewart begins to sing ‘Mandolin Wind’. That song has the most beautiful introduction to it – a guitar, and a banjo and maybe a mandolin. And then Rod’s road-gravel voice, rasping, and raw, breaks out with that opening line –

‘When the rain came, I thought you’d leave.’

And straight away my mind rushes back to those desperate days when the rain came and I thought she might leave.

Teresa is downstairs, in the room below me, right now as I write this. Twenty-two years later, she’s still here with me. I can hear her moving about. Tidying. Talking to the cats. Getting ready. In a while she will call up to see if I am okay. I’ll say, yes thanks, love, down in a minute. And I’ll save my writing, turn off the light and go to meet her.

Join the conversation